Contributed by Poyin Chen

Nowadays you can’t go two months without hearing about a food recall for Listeria or Salmonella contamination. Luckily with our advances in pathogen detection and tracking, we are able to identify and prevent outbreaks before they occur. But what happens when a bacterial pathogen is able to slip by our first line of defense undetected?

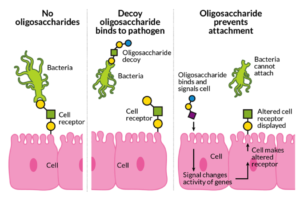

Before a foodborne pathogen can establish an infection in the gut, it must first be able to recognize and bind to the appropriate host cell receptors. This requirement is what allows us to set up our second line of defense using prebiotics. Prebiotics come in many forms and include lipids such as fish oil, and oligosaccharides, such as mannanoligosaccharides (MOS) and human milk oligosaccharides (HMO). These prebiotic oligosaccharides are non-digestible to the host and are thought to work either by providing decoy receptor binding sites for pathogens, or by interacting with host cells to alter the host receptors such that pathogens are no longer able to bind as efficiently (Figure 1).

In vitro studies on the effects of MOS and HMO host treatment prior to bacterial infection indicate that these oligosaccharides may be useful in decreasing pathogen association although the mechanism of protection is unknown. As part of my dissertation studies, I am using a multi-omics approach and enrichment analyses to determine the different gene expression and metabolic pathways that are induced during treatment with MOS versus with HMO. Stay tuned for results!